Most modern packaged based operating systems have a facility for easily allowing remote systems to pull down updates. In the Windows world this is primarily used for distributing bug fixes and security patches through the Windows Update system, although major service packs may introduce new features. In Linux, depending on distribution and configuration, the system may download security and bug fixes, or it may download new versions of software running on the system. In particular, this is useful for running the development versions of distributions.

On Windows the patches typically come with cryptic names and descriptions and don’t provide much of a clear description what they do. A patch is incremental against a known state of the operating system and includes logic to update to the new state. On Linux the updates come as complete new packages that can be independently installed. While this removes some of the dependency issues and allows one to install the updates as a complete package, it is often wasteful, especially when the system is going through massive updates as is the case right before major system releases. For example, here’s what was presented to me this morning:

:::shell

[patrick@hedgehog] sudo apt-get upgrade

Reading package lists... Done

Building dependency tree

Reading state information... Done

The following packages have been kept back:

linux-headers-generic linux-image-generic linux-restricted-modules-generic

The following packages will be upgraded:

alsa-base apport apport-gtk apturl auctex avahi-autoipd avahi-daemon base-files bash bind9-host bzip2 capplets-data

command-not-found command-not-found-data compiz compiz-core compiz-gnome compiz-plugins cups-pdf cupsys cupsys-bsd

cupsys-client cupsys-common cupsys-driver-gutenprint dbus deskbar-applet displayconfig-gtk dnsutils esound esound-common

evince evolution evolution-common evolution-data-server evolution-data-server-common evolution-plugins flex fontconfig

fontconfig-config fortune-mod fortunes-min gdebi gdebi-core gimp gimp-data gimp-print gimp-python gnome-app-install

gnome-control-center gnome-keyring gnome-panel gnome-panel-data gnome-session gnome-user-guide gstreamer0.10-tools

gtk2-engines-pixbuf gtk2-engines-ubuntulooks guidance-backends hal hal-device-manager hal-info hpijs hplip hplip-data

hplip-doc initramfs-tools iproute irb1.8 iso-codes language-selector language-selector-common libavahi-client-dev

libavahi-client3 libavahi-common-data libavahi-common-dev libavahi-common3 libavahi-compat-libdnssd1 libavahi-core5

libavahi-glib-dev libavahi-glib1 libavahi-qt3-1 libbind9-30 libbz2-1.0 libbz2-dev libcamel1.2-10

libcompizconfig-backend-gconf libcupsimage2 libcupsys2 libcupsys2-dev libdb4.3 libdb4.4 libdbus-1-3 libdbus-1-dev

libdecoration0 libdns32 libebook1.2-9 libecal1.2-7 libedata-book1.2-2 libedata-cal1.2-6 libedataserver1.2-9

libedataserverui1.2-8 libegroupwise1.2-13 libesd-alsa0 libesd0-dev libexchange-storage1.2-3 libfltk1.1 libfontconfig1

libfontconfig1-dev libgda3-3 libgda3-common libgimp2.0 libgimp2.0-dev libglade2.0-cil libglib2.0-cil

libgnome-keyring-dev libgnome-keyring0 libgnome-window-settings1 libgnome2-0 libgnome2-common libgnome2-dev

libgnomevfs2-0 libgnomevfs2-bin libgnomevfs2-common libgnomevfs2-dev libgnomevfs2-extra libgstreamer0.10-0

libgstreamer0.10-dev libgtk2.0-0 libgtk2.0-bin libgtk2.0-cil libgtk2.0-common libgtk2.0-dev libgtk2.0-doc libgutenprint2

libgutenprintui2-1 libhal-dev libhal-storage-dev libhal-storage1 libhal1 libisc32 libisccc30 libisccfg30 liblwres30

libmetacity0 libmono-accessibility2.0-cil libmono-cairo1.0-cil libmono-cairo2.0-cil libmono-corlib1.0-cil

libmono-corlib2.0-cil libmono-data-tds1.0-cil libmono-data-tds2.0-cil libmono-dev libmono-microsoft-build2.0-cil

libmono-peapi1.0-cil libmono-peapi2.0-cil libmono-relaxng1.0-cil libmono-security1.0-cil libmono-security2.0-cil

libmono-sharpzip0.84-cil libmono-sharpzip2.84-cil libmono-sqlite1.0-cil libmono-sqlite2.0-cil libmono-system-data1.0-cil

libmono-system-data2.0-cil libmono-system-runtime1.0-cil libmono-system-runtime2.0-cil libmono-system-web1.0-cil

libmono-system-web2.0-cil libmono-system1.0-cil libmono-system2.0-cil libmono-winforms2.0-cil libmono0 libmono1.0-cil

libmono2.0-cil libnautilus-extension1 libncurses5 libncurses5-dev libncursesw5 libnotify1 libopenal0a

libpam-gnome-keyring libpanel-applet2-0 libpanel-applet2-dev libpcap0.8 libpng12-0 libpng12-dev libpng3 libpoppler-dev

libpoppler-glib-dev libpoppler-glib2 libpoppler2 libreadline-ruby1.8 libruby1.8 libsane libsane-dev libservlet2.4-java

libsnmp-base libsnmp10 libssl-dev libssl0.9.8 libtiff4 libtiff4-dev libtiffxx0c2 libtotem-plparser7 libuniconf4.3

libvolume-id0 libvte-common libvte9 libwvstreams4.3-base libwvstreams4.3-extras libx11-6 libx11-data libx11-dev libxml2

libxml2-dev libxml2-utils liferea linux-generic linux-kernel-devel linux-libc-dev linux-restricted-modules-common

linux-sound-base lsb-base lsb-release m4 mencoder metacity metacity-common module-init-tools mono mono-common mono-devel

mono-gac mono-gmcs mono-jay mono-jit mono-mcs mono-runtime mono-utils mplayer nautilus nautilus-data ncurses-base

ncurses-bin ncurses-term ntp ntpdate openssh-client openssl poppler-utils ppp preview-latex-style python-apport

python-avahi python-central python-gnome2-extras python-gtkhtml2 python-launchpad-bugs python-libxml2

python-problem-report python-vte python-xml python2.4 python2.4-minimal python2.5 python2.5-dev python2.5-doc

python2.5-minimal ruby1.8 ssh-askpass-gnome synaptic system-config-printer tasksel task

xserver-xorg xserver-xorg-input-all xserver-xorg-vide

Do you want to continue [Y/n]?

This update was going to download 295 packages that were around 180MB. It actually claimed to free up some space on my hard drive when it was done. Luckily, I was on campus so the download actually went pretty fast. But, really, what was being accomplished? Was it really necessary to download 180MB of updates for changes that aren’t even perceptible to me? I decided to find out.

Before performing the system update I got a list of all the files to be updated and saved a copy of the information. I also calculated the md5sums of the files and saved the file size for each file in each package to be updated. Next, I ran the system update and got a list of the files from the new packages, md5sums, and size of the files. I compared the two sets of information to see what files were actually updated, what files were new, and what files were removed. Finally, I made a “dummy” archive of the updated and new files by copying them into a directory and calculating the size of a tarball of those files. This is a rough estimate for the size of a incremental package.

The total size of all packages downloaded was 160.33MB, when unpacked these files took up 452.37MB, versus 476.14MB before the update; about what apt indicated I would save. However, this is not the complete story. apt caches the previously downloaded files in /var/cache/apt/archive. In reality, my drive now has an extra 136.61MB of data stored on it because of the saved packages. Although, it is safe to delete those packages in most cases.

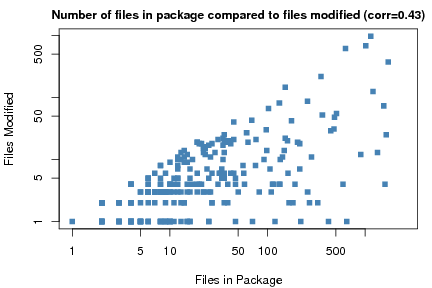

While drive storage is a concern, it’s actually pretty minor. Drive space is really cheap and a couple of hundred megs here or there don’t make much of a difference. However, transferring all that data is what consumes my time. Surely it’s not the case that everything in each one of those packages was new. To examine this, I plotted the number of files in the package versus the number of files the incremental update modified. The correlation is 0.43, which isneither high nor low – some correlation is to be expected because the number of modified files can never go higher than the number of files in the package. The fact that the correlation isn’t higher means that many packages are sending files that don’t need to be updated.

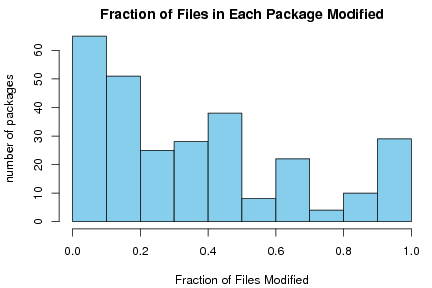

For many people, correlations and log-log plots may not be the most helpful in understanding what is going on, so lets visualize this another way. Below is a histogram showing how many packages had what percentage of files modified. It’s pretty clear that most packages had only a small fraction of files modified. In many cases, 80% of the files transmitted had no changes at all. Multiply that across multiple incremental updates, and that’s a lot of wasted bandwidth and disk space.

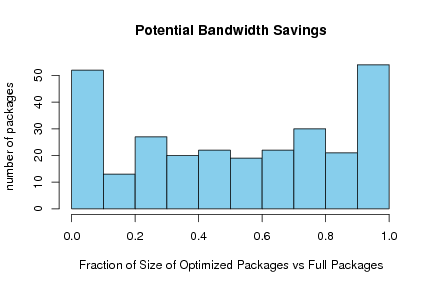

After seeing the histogram, some folks will argue that updates are more likely to larger files, so we’re not really wasting as much bandwidth. After all, looking at many packages, such as bash, the largest files are often binaries and libraries – those that are most likely to be changed in the incremental updates. To understand this, I wrote a script to create dummy incremental packages. Basically, I copied all of the files that were modified into a new directory, created a tarball of the files, and examined the size of the executable. This is only a rough estimate of the size as I did not create a dpkg, so it’s missing the associated overhead there and estimates of bandwidth saved may be a bit optimistic.

The total size of all the dummy packages was 76.35MB, a savings of almost 84MB, or 53% of the original size. It’s like a double speedup in your download speeds. In addition, we save a bit a disk space, and the bandwidth requirements for update sites are diminished significantly. Not all updates compressed the same amount, as shown below.

About a sixth of the smaller packages would be under 10% of the downloaded package size, while another sixth of the packages would have little change in their size. The rest of the packages have a pretty uniform distribution.

What I’m proposing here is a form of incremental packaging – it’s apparently one of the key features of the Foresight Linux. Their system is built on top a pretty cool packaging system called conary, but I don’t think that Ubuntu will adopt it any time soon. Debian folks will consider it to be some kind of conspiracy and either choose not to implement a change, or it will take them 10 years to do it.

There may be a way to accomplish this with the only slight modifications to the current dpkg infrastructure by taking some hints from digital video compression. In video compression, the entire frame is not encoded from one frame to another, rather only the incremental changes are stored. Once in a while, depending on configuration usually from every 0.5 - 3 seconds a key frame comes along. This key frame is a complete re-encoding of the image and the next frame is based off the changes from the key frame. The process repeats until the next key frame comes along.

This results in some great compression especially when the changes in a scene are small, however can take a hit when changes are significant. That’s why if you look closely at HDTV signals in action films you can see some little blocks. Basically the encoding is basing it off a key frame and there is a lot of data to re-encode at a low bitrate. I’m simplifying here, but hopefully you get the picture.

As far as dpkg goes, a similar situation could be created. Periodically package managers could roll a new “key frame” version of a package, such as when a new official release of a package is made. When security updates, or bug patches are made, a incremental package would be generated with only the changes from the “key frame” – this differs from digital video in that video works from the last incremental frame. The reason to differ from the “key frame” is because we can’t assume that everyone has obtained the entire stream of packages, like we usually can with video. The information on the “key frame” package name can be stored in the package information and it could be automatically downloaded from the same source.

Here’s where it could get interesting. When first installing a package, you’ll end up taking a bit of a hit if you’re not installing a “key frame” because you’ll need both the incremental package and the key frame. However, when upgrading you’ll save some nice bandwidth.

The astute reader may note that this requires you to keep a copy of the “key frame” package around, which makes some of the savings a little moot. There are a couple of different ways to address this. One is to create an archive cache on the system. When an incremental package makes modifications to a file from a “key frame” package, the original “key frame” version would be saved and probably compressed somewhere. Then when upgrading to a new incremental package, dpkg would roll back the last package and apply the new one. The roll back configuration means we won’t have to save files from an incremental package that another incremental package modified. Another option is to keep a listing of the files changed somewhere and download the “key frame” package if there are enough changes that the incremental package can’t deal with it.

As far as distributing the operating system on physical media, this change shouldn’t make any difference – all of the packages on the CD/DVD would be “key frames” that work independently. When upgrading and applying security fixes we’d save a lot of bandwidth. However, a down side is that such a technology is not very well suited for locations with very low bandwidth as an incremental package without a “key frame” is rather useless. I haven’t quite figured out how this could work with platforms like the OLPC, but hopefully it’s a start.